Interview with Major Jackson

by Ann van Buren

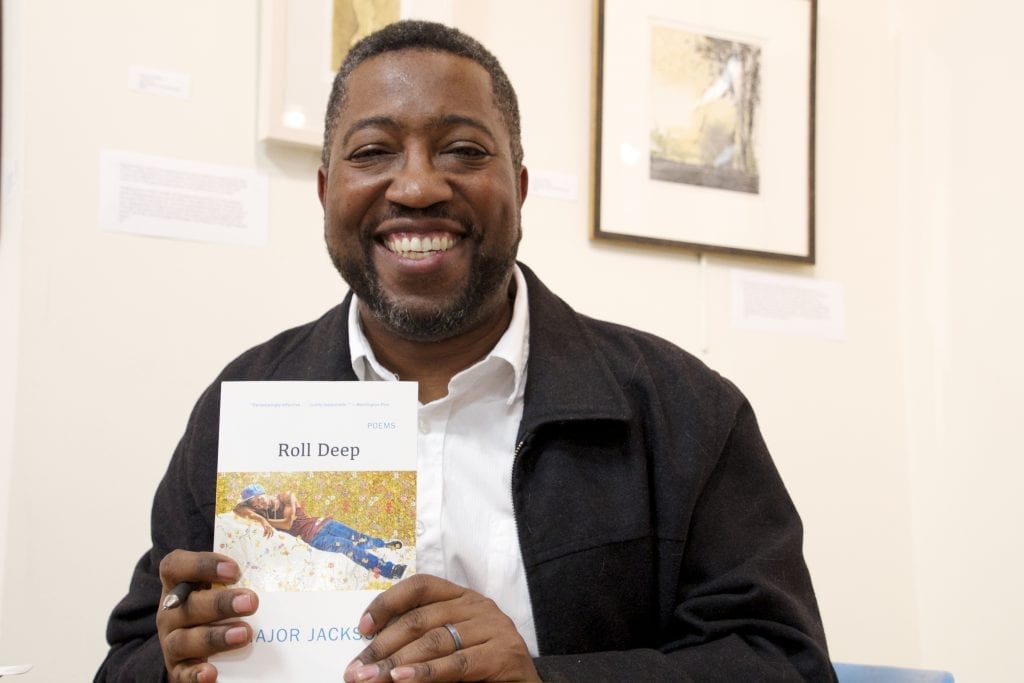

Major Jackson is an American poet, professor, editor, and the author of four collections of poetry. Roll Deep (2017), Holding Company (2010) and Hoops (2006) are highly regarded, and the latter two books were finalists for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literature-Poetry. Leaving Saturn (2002), winner of the 2001 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, was a finalist for a National Book Critics Award Circle. Major Jackson has received additional honors from the Pew Fellowship in the Arts and the Witter Bynner Foundation, in conjunction with the Library of Congress. He is also a recipient of the Whiting Writers’ Award.

As curator and editor of Renga for Obama, Jackson invited over 200 poets to practice this collaborative Japanese poetic form as a way to pay tribute to our 44thpresident. Jackson is currently poetry editor of The Harvard Review. He is also editor of the 2019 edition of Best American Poetry. His fifth book, The Absurd Man, is forthcoming.

As an educator and mentor, Major Jackson is the Richard Dennis Green and Gold Professor at University of Vermont. He has served as creative arts fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, a core faculty member of the Bennington Writing Seminars and as the Jack Kerouac Writer-in-Residence at University of Massachusetts-Lowell.

KPS interviewer, Ann van Buren, connected with Jackson, via Skype, to conduct the following lightly-edited interview. All are welcome to hear the poet, in person, at the Katonah Library on April 7th, 2019 at 4PM. Following the reading there will be a Q&A. Refreshments will be served, and books will be available for purchase and signing.

Ann van Buren:Thank you for taking the time from your busy writing and teaching schedule to talk with KPS. I think that you have a family as well, even as you maintain connections to the larger poetry community. For example, you are currently poetry editor for The Harvard Review. What does a typical day look like for you, and tell me—where do you get your energy?

Major Jackson:

Would you be surprised if I told you I had three clones?

(laughter)

AvB: I would believe it!

MJ: A typical morning includes breakfast with the family, of course— my wife and son— one is still remaining in the house. So breakfast and off to work and office hours, like today, although I cleared the schedule this morning. I meet with students where I teach at University of Vermont, and talk with students about their own writing. Then, in between classes and meetings, I might be able to answer a few emails or maybe even possibly visit a writers group. We meet, if not weekly, every other week, and I might squeeze in a few lines if not a stanza towards a poem before we talk about each other’s work. Then I’m probably heading home or, after dinner, preparing to go give a reading somewhere, like this week, at the University of Michigan and in a couple of weeks in Utah. I normally bring work with me. I rarely ever lounge in a hotel room and watch TV. I bring either a manuscript I’m reading by an up and coming poet—and I give them some encouraging words—or an endorsement for a book, or I might be judging a contest. It seems like I have my hands full.

AvB: It does seem that way! Well, it’s valuable to have someone who pays attention to everyone else. But let’s get back to you again. It seems that you always knew that poetry was your calling. In one poem, from Leaving Saturn, being a poet is equated with having “the tongue of God.” How does that resonate with you? Does this reference go back to the poetic tradition of the African griot, or priest? Or is this an allusion to something else, another spiritual or religious tradition?

MJ: Well, that’s a complicated question. I guess the incarnation of that thinking has its roots in growing up as a child in the church. My grandmother was a deeply religious woman who was an evangelist. I was quite bookish as a kid. She and my grandfather pretty much raised me, along with my mother, but they definitely are central to my early life. They had a lot of books, and one phrase I used to love to hear my grandmother use was “The Holy Word.” Of course, that phrase has deep spiritual and biblical references, but for me as a kid, I was able to translate it into the idea that all language, if constructed in an artful and deliberate way, can have meaning that is sacred. So when I first started writing, I felt as though poetry could ascend to that same kind of import; language could ascend to that same kind of import. Of course I’m thinking about the role of the poet in society, whether it’s the Irish bard or the African griot or djali. There’s a place in our communities for the individual who sings the songs, who renders language important, in rituals that carry the memory of their community. I’m always honored to give readings and to be welcomed to libraries, community centers and universities, because it’s less an individual ego-centered activity and more of a thank you for inviting me into your community to share my words and to think about how our lives intersect through poetry.

AvB: That’s very beautiful, and indeed the Word is central to all cultures. Most certainly to Western culture. “In the Beginning there was the Word,” right?

MJ: That’s right!

AvB:Was poetry an unusual path for a young man coming of age in North Philly in the 1970’s and early 1980’s? What recommendations would you give to young people living there today? Do you think that poetry and art have the power to play a positive role in their lives, and beyond?

MJ: Oh yeah! Yes. In any community, someone can decide that they want to undertake poetry, not necessarily as a profession, but as a vocation, meaning that one could just as easily write law briefs or work in a laboratory and still write poetry. I don’t see it as something where someone necessarily has to give up all else. As you know, Dr. William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, and many other poets made a living doing another job while they were also poets. So I guess I’m in the habit of encouraging people to take up writing poetry. It is an opportunity to slow our day down and to be reflective and contemplate our space in the world and how the world affects us. That practice of putting down language in meticulous fashion, as a mode of inquiry to discover how we feel and how we respond to the world, or even simply language as material—something to kind of tinker with— I believe has a profound psychic, psychological and physiological effect. It’s a way to take care of ourselves. For those young people in North Philadelphia, at least for me, there was so much going on around me that I could not fathom. Poetry, with its ability to urge us towards a condition of inwardness, allowed me to make meaning in a way. So no matter the community, I’m in the habit of encouraging everyone, no matter their age, to take up writing as a way to give a portrait of our inner selves out in our lives.

AvB: I’ve had a few visits to Philly recently. Each time I go, I enjoy the murals there. Was Mural Arts Philadelphia around when you were growing up, and did the murals that they organize inspire you? I think there’s a mural currently being planned out for your old neighborhood of North Philly.

MJ: Yeah. It used to be called the Philadelphia Anti-graffitti Network. Jane Golden turned it into the Philadelphia Mural Arts Advocates, and it transformed the city. Just as I was leaving Philly to go to grad school in ’97, they were under way. I was able to see that program blossom and watch the city become a canvas. The process is democratic in that they ask the community—they don’t just go into the community and throw up anything— but they ask the community and meet with community leaders and ask what’s the image they want to represent them. I think it’s just extraordinary. My favorites are near the library, where there’s a young beautiful black girl reading a book, and then there’s the John Coltrane mural, and right near Temple University, my former teacher, Sonia Sanchez, has a mural off of Broad Street. It’s a stunning project. I wish I lived in Philly!

AvB: It certainly is a great place. Two of the things I love most about the city are the artists you mentioned, and also Sun Ra. Reading your work inspired me to go back to Sun Ra’s music, and I’ve been pulling out my CD’s and listening again. I’m wondering, did you go to hear Sun Ra’s Arkestra when you were growing up, and do you still go back to Philly? The Arkestra, without Sun Ra, is still there.

MJ: My mom and stepdad live in Germantown, not too far from Sun Ra’s house, and occasionally I would bike in that neighborhood and hear music being rehearsed at that house, in his home. But I wouldn’t see Sun Ra perform until later, during my college years and after college when I worked for the Painted Bride Art Center and Sun Ra would perform. It was a tradition for them to perform New Year’s Eve. I was part of the tech team that set up the stage and lights and I worked the sound board. It was transformative to see Sun Ra play, and Marshall Allen, John Gilmore, and I think June Tyson as well. Sun Ra’s niece, Rhoda Blount, also performed with them. I found it to be very transformative. Like many artists today who fall under the umbrella of Afro–Futurists—Sun Ra was one of the earliest—they give license for black people to occupy other kinds of subjectivities or identities and kind of nerd out on sci-fi. There’s the outer-spaceness that Sun Ra models for Afro-American artists and people and the music itself is extraordinary in terms of avant-garde jazz, jazz aesthetics. It’s always been an important part of my listening pleasure.

AvB: Gwendolyn Brooks was important in introducing you to the poetry world, wasn’t she?

MJ: Yes, and no. I guess I was already on a journey as a poet, but there was a moment when I worked at the Painted Bride center when she was invited to give a reading and she came, by train. She famously did not fly. She took a train to Washington DC to receive the Jefferson Lecture award and was on her way up to NY, to give the same lecture for either the Poetry Society of America or the Academy of American Poets. She stopped in Philadelphia to give a reading. I hosted her, and instead of taking a train, she asked if I would drive her. Several friends and I drove her up to NY from Philadelphia. It was an hour and a half of pure bliss! In talking with her, she knew we wrote poetry and asked us to read poems at this event. Then she paid us, afterwards, out of her own pocketbook. I wish I had that check now! It would be worth far more, far more than the cash I needed to pay my rent at the time. I couldn’t believe it. She wrote us a five-hundred-dollar check. In 1996 that was a lot!

AvB: Very magnanimous! What a great story. You’ve had interactions with so many artists and poets. I’d like to hear more about your collaborations, but I’m also interested in the particularity of the moment when your reflections on another artist’s work generates writing of your own. I wonder if you can describe that experience.

MJ: I feel so indebted to the musicians and playwrights, screenwriters, film directors, visual artists, sculptors I can say that I grew up with, as a kid, because my aunt worked at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I grew up going there as a kid through my high school years and even beyond. I’ve always had this alternative education or look on the world that has shaped me in so many ways. Much of it is an indebtedness. If I write about Sun Ra or write about John Cassavetes or any of the filmmakers, there’s a sense of indebtedness. But there’s also a transcription of my experience with the art. It’s a way for me to map my intellectual and emotional response. In the case of Sun Ra, when I was writing those poems I was deeply immersed in his music as well as his biography, written by John Szwed, the ethnomusicologist. So it was pure immersion. I don’t think I’ve since immersed myself. Maybe I felt I had overwhelmed my composing imagination with too many facts about Sun Ra’s life that I just gave up on that and realized that that’s not the method for me— to do that much research— but to try to take what little I do know and then inhabit Sun Ra’s consciousness. I was writing these dramatic monologues and hadn’t written any of them for a while, but I think that one of the last poems in Roll Deep, was written in his voice.

AvB: Yes, “Energy Loves Here “.

MJ: Yes, “Energy Loves Here”.

AvB: I like that poem a lot. You inhabit the style of Sun Ra. The stops and the starts and line breaks in unusual places remind me of Sun Ra.

MJ: Thank you.

AvB: Can you recall when you were writing “Energy Loves Here?” It’s difficult when one is inspired by another artist’s work to avoid being descriptive or referential or academic about it. This poem is very embracing because it seems to be pulling things from the imagination, from the ether, the air, and putting them together not in a grammatical ordinary kind of language. How do you get to that place where you’re free enough to write that spirit?

MJ: (laughter) That’s a good question. You know, it’s funny, I have to trick my mind into another space. When I was younger, it was playing music really loud. Not really loud, but loud enough to block out anything else and absorb the energy of the music. In the case of Holding Company, for example, I was listening to a lot of the jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal. But how do I get to that place? You can rest assured that I don’t just sit down and I’m there. It takes absorbing other poems. I read a lot before I start writing, and spend time listening to music. Normally those are the two paths. There even was a moment when I would take morning runs just to get the endorphins going and get into this energetic space. Writing for me has never been Wordsworth’s— what’s that line? — “recollections in tranquility.” It’s been a far more terrorizing space to be in. So when people ask about creative process, it’s far more demanding of me physically and emotionally. I don’t sit down at my desk and there’s a cup of tea and the window’s open to spring and trees and birds are flying by. It’s far more demanding and maybe even violent, because I find language and all that they signify kind of clashing together like the jazz suite or a symphony harmonious. Maybe that’s it. Maybe it’s— what’s the word, the word where you mix the senses—

AvB. –Synesthesia.

MJ: Yeah, it’s far more synesthetic. It’s not just words or semantics, it’s quite demanding.

AvB: Thank you. That was a nice stroll through your mind!

(laughter)

AvB: So being in Vermont is not exactly what’s feeding your imagination?

MJ: It’s a nice backdrop. I definitely take advantage of being in the outdoors and get a lot of hikes in in the summer, do a lot of kayaking and even get out in the winter. I don’t ski or snowboard. My children do, but I go in the woods snowshoeing and am in the habit of not collecting, but trying to identify as much of the fauna and flora around me.

AvB: That’s an interesting thing, especially since it’s in danger.

MJ: Yes, that’s right.

AvB: Well, I’ve got so many things to ask but I know you have to go teach soon, so I have to choose carefully. About the book Holding Company— What made you write almost every section in 10 lines? I think I’m on the wrong track, but I wondered if you were writing décimas?

MJ: I was asked to write a poem about the 10thanniversary of Cave Canem. That would have been 2006. I really liked writing that poem, and I undertook it as a project mainly because I was surprised at the compression and how words, even in that small space, can echo out so much more and insinuate so much more than what is said on the page.

AvB: I heard you read one of them in an online recording and noticed that play between compression and expansion.

Another thing I noticed about your work is that it often leaves an impression of the urban space. But in Roll Deepyou are all over the map, literally. You are in Italy, Greece, Kenya. What brought that about?

MJ: I am so fed by travel. Even in, I think it’s Hoops, you can find writing about a trip I took to Ireland. I just thought it would be great to get them all in one. That’s a project where I’m writing in not quite a prose block but the extended sonnet in somewhere between 16 and 20 lines. I think the longest might be 24. It comes from my series “Urban Renewal,” which I began in Leaving Saturn. Those poems are in Leaving Saturnand Hoops,not in Holding Company.They come back in Roll Deepand in the book that will be out next year, The Absurd Man. Urban renewal poems appear there, too. Much in the same way that the visual and performance arts, literary arts, have informed my world, I have been fortunate to travel to slightly under a dozen countries. I am always surprised by the correspondences.

AvB: It’s interesting that even when you’re on another part of the globe, your poetry brings you back home. I was particularly struck by section iv of your poem about Kenya. It has the subtitle, “Tour of the Food Distribution Point, Ifo.” In it you say:

…They wait for the First

of the Month like the poor in Detroit, a flea bite solution

in the fight against famine…

Can you talk about this? It’s wonderful for somebody in art to address our food system and its problems.

MJ: This was a refugee camp in NE Kenya, close to the border of Somalia. Well, it’s surprising that still, in the 21stcentury, there are many parts of the world where we have not figured out how to address hunger. Granted these were primarily war refugees, and the World Food Program, to which the US gives quite a bit, participates. But, it’s not a big leap for me to think about the fact that the rationing, the food rationing, happens on the first of the month, in the same way that people who are on public relief have to wait a month, a month to get food. It wasn’t a big leap for me. This is what I think is important about being an international artist. It’s almost a responsibility for us to represent humanity writ large. What are our common struggles? What are our common joys? What do we celebrate and what presents itself as an obstacle to all of our dignity? This happened to be one of the obstacles I recognized, because we suffer poverty in the US, but people suffer poverty in other parts of the world as well.

AvB: Another parallel is the adage “Give a man a fish and he eats for a day, teach a man to fish and he eats for a lifetime.” We don’t want to take away these programs that supply food, but there’s something kind of systemically backwards about band-aid relief.

MJ: That’s right.

AvB: So I really appreciated the parallel between a war-torn land, and Detroit, where the means to survive has been destroyed, down to the last drop of clean water.

MJ: That’s right.

AvB: I’m thinking of the recent honoree of the PEN prize in poetry,Jonah Mixon-Webster. He writes very powerfully about the Detroit crisis. I wonder who are some of the young poets, or old poets, you would like us to look out for.

MJ: I’m always reluctant to pick favorites because I know I will leave someone out. But there are a few former students, Javier Zamora, Morgan Parker, and Solmaz Shariff were all in a seminar that I taught at NYU in various different years. I’m very proud of them. I take no responsibility whatsoever for their talents. They did not workshop with me but they’re brilliant young poets. Actually, Javier did workshop with me at a writer’s conference in Squaw Valley. But there are poets I’ve met and know, who I think are just coming up and who are extraordinary. I’m reluctant to name names, but having recently edited Best American Poetry, which will be coming out in September, I have a bird’s eye view of the reach and depth of American poetry. I feel very moved and comfortable with the future direction of American poetry. Its width is not to be underestimated. My hope is that we have critics who can come along and appreciate the diversity of the poetry and speak to its value and worth. I think the poets always outrun the critics. Sometimes our standards of appraisal and what we are taught to value seems— the tools— seem comparatively inept.

AvB: What would you like to see people value more? What tools would you like to see used?

MJ: The cultural richness of the poetry, not necessarily line breaks and metaphors, but the deep humanity from which these poems emerge. Sometimes if that cultural richness is foreign to one, then it doesn’t rise to the occasion of art. That’s always been the stance of some of our most professional poets. I’m strongly advocating two things. One, that we develop a national holiday for poetry—and not for literature—but for poetry. I know we have World Poetry Day, but in the US, the poets and the various traditions by which we have evolved are pretty phenomenal, I think. Secondly, I would like to see us embrace and celebrate—formally, through prizes— that strand of American poetry that protests, bears witness, calls attention to issues and injustices, social and otherwise. We have a long tradition of protest poetry in this country and it would be a way of celebrating our liberties and our freedoms if we acknowledge that.

AvB: Well, here’s to that kind of celebration. I’m with you!

We’re really looking forward to your reading on April 7, and thank you for sharing all of this with KPS.

MJ: Thank you!